Vol. 10, No. 2 • May 2006

Protecting the Health of Children and Teens in Foster Care

Sometimes the child welfare system is so focused on child safety that we forget to talk about—and address—the physical health needs of children in foster care. This, despite the fact that as a group, foster children are sicker than other children, sicker even than homeless children and children living in the poorest sections of inner cities (GAO, 1995).

Research findings on this subject are alarming. For example, Dicker, Gordon, and Knitzer (2001) report that among children in foster care aged birth to three:

- Nearly 40% are born low birthweight and/or premature, two factors which increase the likelihood of medical problems and developmental delays.

- More than half suffer from serious physical health problems, including chronic health conditions, elevated lead blood-levels, and diseases such as asthma.

- Dental problems are widespread: one-third to one-half of young children in foster care are reported to have dental decay.

- Over half experience developmental delays, which is four to five times the rate among children in the general population. A study of over 200 children in foster care under the age of 31 months found that more than half had language delays. By comparison, only 2-3% of preschoolers in the general population experience language disorders, and only 10% to 12% have speech disorders.

Dicker and colleagues also note that nearly 80% of very young foster children are at risk for a wide range of medical and developmental health problems related to prenatal exposure to maternal substance abuse.

Older kids in foster care don’t fare much better. McCarthy (2000) found that 80% of children in foster care have at least one chronic medical condition, and that 25% have three or more chronic problems. Children in foster care are also more likely than kids in the general population to suffer from acute health problems such as tuberculosis and sexually transmitted diseases (Grayson, 2003). These problems are often worsened by lack of continuity of intervention and recordkeeping and declining emphasis on preventive measures as they enter adolescence (Nixon, 2002).

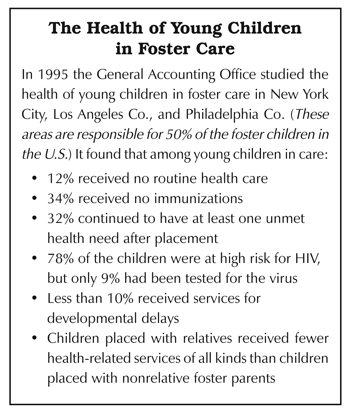

Despite the fact that we know their health is vulnerable, too many children in foster care fail to receive services to address and reduce the risks they face. As the U.S. General Accounting Office learned in a large-scale study in 1995, a significant percentage do not even receive basic health care, such as immunizations, dental services, hearing and vision screening, and testing for exposure to lead and communicable diseases (see below). Specialized needs such as developmental delays and emotional and behavioral conditions are even less likely to be addressed (Dicker et al., 2001).

Disruption plays a role, too: moves often lead to changes in physicians, social workers, schools, and other providers, which can produce health care that is inconsistent and without focus (Grayson, 2003).

The Child and Family Services Review

To address this situation and to comply with the Adoption and Safe Families Act of 1997, the federal government recently assessed states’ efforts to safeguard the health of children involved with child welfare. During the first round of its Child and Family Services Reviews the federal government concluded that only 20 of the 50 states did an adequate job of meeting the physical health needs of children involved with child welfare (USDHHS, 2006).North Carolina was one of these 20 states. Reviewers approved of North Carolina’s health-related child welfare policies, especially those that require children to be referred for a physical examination within one week of an initial placement and that require children identified with a need for dental, developmental, or psychological assessment to be referred within one week from the identification of the need.

Federal reviewers also found that in the vast majority of cases, North Carolina’s social workers comply with these policies. Reviews of case records from 16 counties indicated 92% compliance with the referral for a physical examination and 100% compliance for referral for appropriate assessments when a need is identified.

During site visits federal reviewers found that social workers often go to medical appointments with children and are seen by stakeholders as diligent, particularly in foster care cases. Reviewers also observed that, “Foster parents are involved in and informed of children’s medical care and are seen as very competent and dedicated to helping the children in their care maintain health.”

This is not to suggest that North Carolina is in a state of perfection when it comes to the well-being of children involved with child welfare. Overall, federal reviewers concluded that our state, like virtually every other state in the country, needs to improve its ability to meet children’s physical and mental health needs. Reviewers identified mental health services as a special area of concern in North Carolina.

Our state will probably participate in another federal review within the next year as part of the ongoing national Child and Family Services Review process.

The Link to Early Intervention

When it comes to improving the health of very young children in foster care, one of the most effective things child welfare systems can do is strengthen the connection between child welfare and early intervention (Dicker & Gordon, 2004). Early intervention programs entitle eligible children aged birth to three to a multidisciplinary evaluation and an Individualized Family Service Plan that can include hearing and vision screening and treatment, occupational, speech, and physical therapy, and family support services such as parent training, counseling, and respite care to enable parents and caregivers to enhance the infant’s development.In response to a 2003 federal law, North Carolina now requires child welfare agencies to refer families of children aged zero to three to early intervention services whenever child protective services substantiates child maltreatment or requires a family to accept child welfare services. The referral must be made within 48 hours of the case decision.

Early intervention services are voluntary, so birth families can decline these services if they wish. However, if that child later enters foster care, the child welfare agency has another opportunity to request (and accept) early intervention services on that child’s behalf.

If you are the foster parent of a child between the ages of zero and three, you can help protect the child’s health and development by asking the child’s social worker if that child has been referred to and screened by an early intervention program. These services can make a big difference in a child’s life.

What Can You Do

As we have discussed, in many ways North Carolina seems to be “on the ball” when it comes to attending to foster children’s physical health needs: we have appropriate policies in place, and in most cases they are being implemented.Of course, foster parents play a central role when it comes to protecting children’s health and promoting their development. Examples of their contributions include taking children to medical appointments, staying in touch with various medical providers, and providing the hands-on care that keeps children in good health.

What else can foster parents do?

Foster parents should be aware of North Carolina’s child welfare policies and practices related to health. In particular, they should be familiar with and be on the lookout for the Child Health Status component (DSS form 5243) of the Family Services Case Plan, which documents current critical health information about the child, and for the Child Physical Examination form (DSS form 5244). State policy requires the placing agency provide foster parents with these forms as soon as they are available. You can find a sample of these forms below. If for some reason they do not receive this information, foster parents should request them from the child’s social worker.

The Permanent Judicial Commission on Justice for Children (1999) believes that child welfare systems should consistently ask the following questions for each child in foster care:

- Has the child received a comprehensive health assessment since entering foster care?

- Are the child’s immunizations up-to-date and complete for his or her age?

- Has the child received hearing and vision screening?

- Has the child received screening for lead exposure?

- Has the child received regular dental services?

- Has the child received screening for communicable diseases?

- Has the child received a developmental screening by a provider with experience in child development?

- Has the child received mental health screening?

- Is the child enrolled in an early childhood program?

- Has the adolescent child received information about healthy development?

The ultimate responsibility for asking these questions—and for carrying out many of the actions that the questions inquire about—almost always falls on the agency that has custody of the child.

However, as advocates concerned with child well-being, it is appropriate for foster parents to ask these questions as well. Many of them can be answered by reviewing a child’s Child Health Status Component and Child Physical Examination forms. If you still have questions after reviewing these forms—for example, about whether the child should be receiving early intervention services—ask the child’s social worker.

Although some of the information we have related in this article is sobering, we hope that it will help you as you nurture and advocate for the children you care about so much.

Resources for Learning More

Children in Foster Homes: How Are They Faring? A research brief from Child Trends <http://www.childtrends.org/files/FosterHomesRB.pdf>Health Care of Young Children in Foster Care. A policy statement from the American Academy of Pediatrics that gives specific suggestions concerning of health services for young children in care. <http://www.aap.org/policy/re0054.html>

Children Discharged from Foster Care: Strategies to Prevent the Loss of Health Coverage at a Critical Transition. <http://www.kff.org/medicaid/4095-index.cfm>

For additional resources about the health and mental health of children in foster care, visit the National Resource Center for Family-Centered Practice and Permanency Planning <http://www.hunter.cuny.edu/socwork/nrcfcpp/info_services/child-and-adolescent-health-care.html>

Copyright � 2006 Jordan Institute for Families